An allegory of the struggle at KPFA

by Daniel Borgström

Longtime KPFA listeners remember 1999 as the year of the Hijacking, the Lockout, and the massive response. Ten thousand people marched through the streets of Berkeley chanting “Take back KPFA!” and “Save Pacifica!” And, as a matter of fact, KPFA and Pacifica Radio were rescued. The good guys really had won, or so it seemed at the time. But the struggle has continued. Today, in 2015, the future of KPFA/Pacifica is more precarious than ever.

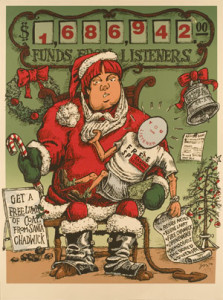

One of the many graphics from the 1999 struggle. Santa holds the listeners like a baby. Beside her right knee, a sign reads “Get a Free Lump of Coal from Santa Chadwick.” It refers to the then Pacifica Executive Director Lynn Chadwick.

Sadly, this KPFA scenario is a common one in the affairs of humankind. I missed the French Revolution, but I imagine it went much like the one at KPFA. The Bastille was stormed in a day, but what followed were meetings, meetings, and more meetings. That’s probably true of all revolutions: there’s a dramatic moment, then months, years, even decades of intense, parliamentary struggle. Issues get complicated, seemingly arcane, and the struggle is vicious; people are sent to the guillotine. Why the conflict? people ask, wondering why the former comrades can’t just be nice to each other and get along.

read more

The KPFA upheaval of 1999 began, very much like the French Revolution, with a split among the power elite. Like Louis XVI of France, the headstrong monarch of KPFA/Pacifica quarreled with her courtiers, threw them out of the palace, locked the gate, and called in mercenary troops — rent-a-cops. The disenfranchised nobility, losing their wits and acting out of sheer desperation, allied themselves with dissidents, appealed to the rabble, and called for mass demonstrations.

The response was huge, and thousands were suddenly marching in the streets. To the astonishment of everyone, the rebels emerged victorious. The intolerable monarch went into exile, leaving the kingdom to the triumphant revolutionaries — a motley assemblage of commoners, peasants and riffraff, together with nobility and bureaucrats from the old regime. Everyone pledged eternal loyalty to the ideals of the revolution, the Mission Statement.

At first there was wild jubilation, dancing in the streets, and a huge amount of good feeling. All the worthy people were dear sisters and brothers, in a splendid state of living happily ever after. The bluebloods and bureaucrats from the old regime joined in the celebrations together with their low-class brethren, graciously tolerating the situation, putting a good face on it, and biding their time.

At first there was wild jubilation, dancing in the streets, and a huge amount of good feeling. All the worthy people were dear sisters and brothers, in a splendid state of living happily ever after. The bluebloods and bureaucrats from the old regime joined in the celebrations together with their low-class brethren, graciously tolerating the situation, putting a good face on it, and biding their time.

The trouble was that the ungracious mob expected to have a say in the running of the new regime. So the lords and ladies were then faced with the daunting task of getting this horde of loud, smelly, cantankerous, meddlesome peasants to leave the castle, go back to tilling the lands, and give up their preposterous notions of involving themselves in governance.

That’s been the basic scenario in just about every revolution on record, and KPFA has been no exception to the pattern. Major differences and animosities began to surface during the drafting of Pacifica’s new constitution, known as “The Bylaws.” Courtiers and bureaucrats from the old regime tried to bend the new document to their liking, intending to preserve whatever they could of their former status and privileges; they did win major concessions. Nevertheless, the dissidents stuck to a vision they’d been nurturing for many long years during the decade preceding 1999. The traditional motto of “liberté, égalité, fraternité” was updated to include “democracy, transparency, accountability.”

The outcome beginning in 2002 was a radically new system of radio governance, a “listener democracy.” Listener-members who donated $25 or more to the station became voters, choosing their representatives to sit on boards overseeing the KPFA station and the Pacifica radio network. In radio governance, this was a revolutionary concept; however the Lords & Ladies found it absolutely revolting.

(The outraged bluebloods are the relatively small clique of gatekeepers who run the station; some have been there for over three decades, others are fairly new. Most of the unpaid staff, who in fact produce most of the programming, are excluded from the ruling clique, as are some of the paid programmers. They’re part of the peasantry.)

There was a time, the good old days, when peasants knew their place. One can sympathize with the plight and anguish of the once proud KPFA aristocrats, courtiers, and bureaucrats, who found themselves sitting shoulder to shoulder with unwashed peasants who had the audacity to ask nosy questions, and worst of all, expect that the station live within its financial means. Peasants can be so intolerably frugal; they want to know how the listeners’ money is being spent.

Money, and how it gets used, misused or just plain wasted, has been an ongoing issue. Programming is another: should KPFA be the voice of progressive social movements? Listener democracy itself is of course among the major controversies: should the board be elected by listeners, or appointed, and if appointed, appointed by whom?

I won’t say more about the issues here, or try to list them, as they’re discussed elsewhere in numerous articles. What I do want to point out is that this struggle was going on long before the events of 1999, and it continues. The basic issues have remained largely the same for the last 25 or 30 years.

In the French Revolution, as in so many others, the aristocrats (or some newly minted aristocrats) were soon back in power. But does it really always have to turn out that way? At KPFA the outlook is not optimistic. Nevertheless, the peasants have somehow managed to hang in there for the sixteen years since 1999, struggling toward a different outcome.

Daniel Borgström is a descendent of European peasants who lives in Berkeley and listens to KPFA 94.1 FM. You can find this article and more at Daniel’s blog.